Last date for submissions

31st October 2022Date of publication

1st December 2022

Abernethy Station And Other Memories

A recent walk down Station Road and a glance over to where the station used to be brought back many childhood memories of what the station was like as l remember it as a laddie seventy years ago. Our family were the local coal merchants and carriers, and with horse and cart carried many of the goods that were delivered to, or left Abernethy by rail. After school or on Saturdays and holidays l would often sit proudly beside my father on the lorry pulled by one of his magnificent Clydesdales. Smiler, Bob and Prince were some of the names l remember but Smiler, a beautiful chestnut with a white diamond splash on his face and four huge, to me anyway, hairy white feet; a gentle giant, he was my favourite. Better still was getting to ride on his back when he would be taken down to one of our fields to graze after work in the summer months. Along with pals it was exciting to go to the smiddy below Margaret Coles’ house at 10 Main Street, or the Tootie corner as we knew it, to see her grandfather shoe the horses. The smell of the burning hoof when the hot shoe was put on lingered in the nostrils for a long time. This really was a smithy under a spreading chestnut tree, and where we got our conkers in the autumn.

At this time much of the produce sold in our local shops, hotel and 2 pubs would still come in by rail and would be delivered morning or afternoon every day. It`s hard to believe, but we had eight shops in the village at that time, all I think worth a mention. Starting at the west end 3 Main street now called the Toll House was “Corstorphines” selling groceries and papers. They were also agents for the bus company and you could have items delivered to the shop to be collected or put on the bus to be taken elsewhere. At 21/23 Main Street was a branch of Newburgh Co-op. Every Saturday morning Jim Shepherd the eldest son of a fine family of twelve who lived at Stewarts Hill farm above Gattaway would come down with his donkey pulling a little two wheeled cart. He would load up with enough supplies to at least keep them going until the Monday when they would be down to school! Next door at 25/27 had previously been "Davie Broomes"’ one of our two bakers which was closed just before the time l am recalling. On the other side of the road now 22 Main Street was Thomson Ramsay the butcher who was also Provost when we had our own Town Council. His front of shop helper was the popular Jean "the butcher" Scott who seemed to forever have a “dreep" at her nose which she normally managed to ”dicht” with the sleeve of her "peenie” just before it dropped into your mince, but occasionally she didn`t quite make it in time. She seemed to manage to cut her finger almost daily and the bandage she used was a piece of paper tied with butchers string. You were never sure whether the blood on the bandage was from Jean or the mince. The butcher meat was delivered from Perth abattoir most hygienically on the back of the Newburgh carrier’s lorry, covered in some hessian sacking. l don`t recall anyone ever suffering food poisoning from eating Thomson Ramsay`s beef. Previously the cattle sheep and pigs would have been slaughtered in a shed behind the shop where the lock-ups are now and my aunt recalled that they knew when a beast had been killed because the washings from the shed floor ran down an open drain from the shed, along the ”shoughie” and into the street drain. If it was a pig being killed the boys always seemed to know and were present to get the pigs bladder for a football. John Smith had a fine grocer’s shop where Brian Greig`s shop is now and two doors further along, now 30 Main Street, was Kate Walker's wee shop that also sold groceries as well as what would then be described as haberdashery. Across the road in the gap between 29 and 31 Main Street was Andrew Wilkie`s bicycle repair shop where he also sold his famous Tower brand cycles. lt would be good to have one in the museum showing the unique rnarque of the Round Tower on its frame below the handle bars. Mr Wilkies`s house next door was where you collected your prescription which the Doctor had brought from the Newburgh chemist. All the prescriptions were just left on a tray on a table in the hall, and you just opened the door and took what was yours. Of course you had a good look to see what everyone else was getting pills or potions for; trusting times. l can`t recall ever hearing of anybody`s medicine being stolen. Where the clinic is now was ”Ritchies” the largest of the grocery shops and when he retired it became the Co-op. I can remember seeing large blocks of ice being carried up the close from the Perth Ice Factory lorry for his ice cream machine in the back shop where previously there was a snooker table where the men could go for a game. Across the road, now 61 Main Street, was John Clark`s busy bakery. l remember being sent for a half loaf (why was it always called a half loaf when it was in fact a whole loaf) and getting one still warm and picking bits out of it to eat before getting home. Finally across the road again, now 56 Main Street, was Norman Peddie`s post office which also sold groceries, papers and some hardware. Years later l would twice work as an auxiliary postie at Christmas time. We delivered to an area stretching from Greenside Farm in the east to Balmanno in the west and all the hill farms, all by bike. I picked up extra mail and parcels at the small post office at Aberargie which had a hand cranked petrol pump outside. The two worst deliveries were to Stewarts Hill farm, which meant leaving the bike at Craig Haxton`s farm at Greenside and walking the half mile up a track beside the burn to Stewarts Hill, and to Barclaylield, away up at the back of Ayton House. lt is now a much better track and part of the Castle Law circular walk. Abernethy also had a cobbler’s shop at West Park and a barber’s at the corner of Station Road and Cluny Street. At the house beside that Mrs Richardson made kilts and a Mr Fairfoul had several ladies who made fur-lined ladies gloves in the hall of the church in Kirk Wynd before the hall was destroyed by fire. The fur came from fancy coloured rabbits which he bred in a shed down Cordon Road. So you will see it was quite a metropolis, and up to this time most of the requirements were coming in by rail, although this would soon become less and less as road transport slowly took over. What is now The Old Town House in the square was indeed the Town House where the ”Toon Council" would hold its meetings upstairs while the Library and the childrens’ clinic, presided over by our redoubtable Nurse Peattie, was downstairs. Upstairs was also the Registrar’s office where John Smith the grocer acted as registrar for births, deaths and marriages including the marriage of Liz and me in 1967.

Back to the station where smaller items would be sent down a shiny metal chute from platform level to the loading bank at the road side in front of what is now Mitchell Shaw`s house but which was previously the station office. At that time it would be boxes of butter which would be cut into required portions in the shop by the shop assistants with wooden butter ”pats " and wrapped in paper. Large cheeses had to be cut with the wire cheese cutters. Sugar, lentils, dried fruit and other items would come in bulk and have to be weighed and bagged in the shop. Larger items like bags of flour for the bakers, barrels of beer and boxes of spirits for the pubs and hotel would be unloaded from the vans in one of the three sidings on the north side of the bridge. The contents of the barrels were poured using gallon measures in to the tins which you brought to the shop. All measures and weights had to be taken to the hall once a year when the weights and measures inspectors would check them and put a stamp on them to show that they were up-to-date and accurate. Steelyards from the local farms and all the scales used at the berry picking would also have to be brought in on that day. These sidings were also where the wagons of coal would come in. As well as deliveries to households which were all heated by coal fires, there was a regular supply to the local gasworks situated at the far end of Cluny Street but which closed down shortly after the time l am writing about after a fire. The last manager/engineer was a Mr Sinclair whose duties as well as producing gas was to collect the money from the meters. Anecdotal evidence suggests that in the days after collecting said meter monies Mr Sinclair would occasionly go on a two or three day bender, with the result that the burgh would have no gas. This was winter time, cold and early dark, so with no heating or light the lieges tended to retire earlier than usual. Unequivocal evidence proves that nine months later Abernethy witnessed a spike in the birth rate, substantiated by the fact that in my year at Abernethy school we had seven pupils in my class with birthdays in the same week. l was not one of them. l am not aware if any had Sinclair as a middle name.

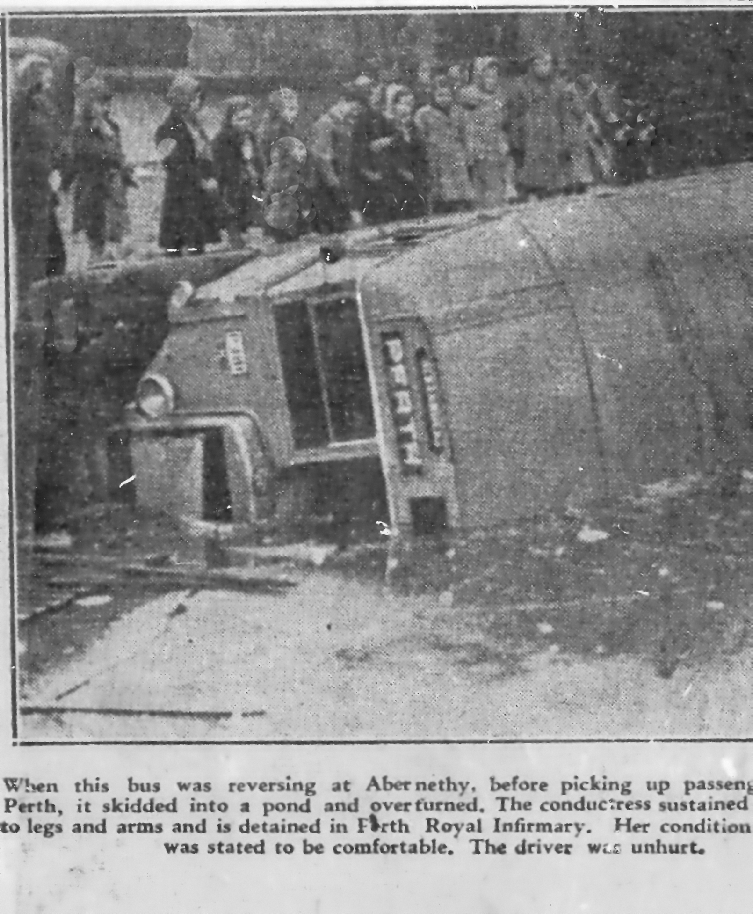

A seventy eight year old memory can be hazy at times but l think l can recall when Abernethy had gas street lighting lit each evening in the winter time by the local ”scaffie”, Geordie Beatson, whose duties also included digging the graves and ringing the "bairn’s bell“ at eight o`clock every night on the Steeple bell to let you know it was time you were home from the den or the park or wherever you were playing. The Round Tower was always ”The Steeple " l think the only remaining evidence of our gas street lighting is the pole at the entrance to the Hall car park. Hint hint to the excellent Abernethy in Bloom committee, might it not make a fine point for a flower basket? Where Branston’s potato plant is now was originally a linen factory and this would need supplies of coal to fire its steam engines working the mill. The original tall "factory lum” still stood at this time as well as the factory pond, where there is now a fine old horse cart flower display, which  provided the water for the steam engines and was a favourite place for we boys to catch frogs, newts and sticklebacks. Also a place of great excitement around 1950 when a bus turning there to go back to Perth slipped into the pond. l could be in the photograph of excited onlookers. During the war these buildings were used by the Ministry of Food as a factory to make cheese. I don`t know if any of the milk supplies for this purpose came by rail or if any cheese went out by rail. To my generation it was always “The Cheese Factory” where we would climb up the drain pipes and run back and forward over the roof ridges, with no thought of ever falling through one of the many glass roof windows.

provided the water for the steam engines and was a favourite place for we boys to catch frogs, newts and sticklebacks. Also a place of great excitement around 1950 when a bus turning there to go back to Perth slipped into the pond. l could be in the photograph of excited onlookers. During the war these buildings were used by the Ministry of Food as a factory to make cheese. I don`t know if any of the milk supplies for this purpose came by rail or if any cheese went out by rail. To my generation it was always “The Cheese Factory” where we would climb up the drain pipes and run back and forward over the roof ridges, with no thought of ever falling through one of the many glass roof windows.

The next use of the buildings would the first of it being used for potato storage, and much of the seed potatoes handled there would go out by rail to growers all over the country. The bags of potatoes would be transferred to the station on small platform trailers pulled by Scammell electric tractors. This was all done in the winter months and the rail vans would need to be lined with bunches of straw brought in from local farms to protect the potatoes from frost damage while in transit. lf the weather was very severe then transport would be stopped. Sugar beet was another agricultural produce sent by rail to the sugar beet factory at Cupar. This and other bulk loads would be weighed on the weighbridge which was situated next to the fence bordering Mr and Mrs Banks house opposite the park gate. You can still see a small area of cobble setts where it stood. Some of the farms and big houses would take their coal supplies in bulk and they would also be weighed here as well as coal for the school. Our school at that time had four teachers and not that many less pupils than at our present school, which has l believe around thirty staff, but oor teachers each had a belt and l am sure this was a great aid in managing pupil/teacher ratios!

One of the most regular deliveries from and to the station was from Robert Clow and Company`s factory, where Clow Square is now and which made high quality l

One of the most regular deliveries from and to the station was from Robert Clow and Company`s factory, where Clow Square is now and which made high quality l adies nightwear. The bolts of cloth to make the garments would come in by rail and the boxes of finished goods would be sent to top shops in cities all over Britain, like Jenners in Edinburgh and Harrods in London. Other boxes would go to the docks to be sent to Canada and the USA and some of the Scandinavian countries, under the Fair Maid brand name. The factory in its heyday employed many women and young girls from both Abernethy and Newburgh as you can see from the photograph. lt would be on one of his regular visits to the factory with his horse and cart that a young Arch Bett would first set eyes on the bonniest one of them all, Annie Hutton from Newburgh, and they would be married in 1925.

adies nightwear. The bolts of cloth to make the garments would come in by rail and the boxes of finished goods would be sent to top shops in cities all over Britain, like Jenners in Edinburgh and Harrods in London. Other boxes would go to the docks to be sent to Canada and the USA and some of the Scandinavian countries, under the Fair Maid brand name. The factory in its heyday employed many women and young girls from both Abernethy and Newburgh as you can see from the photograph. lt would be on one of his regular visits to the factory with his horse and cart that a young Arch Bett would first set eyes on the bonniest one of them all, Annie Hutton from Newburgh, and they would be married in 1925.

One of the most important exports from Abernethy was the raspberry crop. From the early part of the 20th century Abernethy was literally surrounded by raspberry fields where around ten, mostly small, growers produced possibly as much as 100 tons of raspberries in a season. This would be dispatched by rail to several small jam factories in Blairgowrie and Dundee. This all changed during the First World War. Up to that time no raspberry jam was issued to our troops as it was considered that eating raspberry jam greatly increased the risk of someone getting appendicitis. This medical opinion dramatically changed in 1917 when the Government then commandeered the entire country`s crop of rasps for jam production for the troops. This seemed to be more to do with the failure of the plum crop that year, which had previously been the main source of jam for the troops, than any medical evidence to prove there was no longer any great risk of appendicitis from eating raspberry jam. This cartoon from the "Bulletin” newspaper of the time lampooned the  Minister who issued the orders. As production of fruit increased in the years leading up to the Second World War most of the crop was dispatched on a daily basis to

Minister who issued the orders. As production of fruit increased in the years leading up to the Second World War most of the crop was dispatched on a daily basis to  Hartleys jam factory in Liverpool. The berries were transported in 1 cwt (112 pounds) wooden barrels which had previously been used to transport salt herring from many of the east coast fishing ports, to the Baltic countries. The barrels went south on the late afternoon train and the empties returned next morning. This trade would cease during the war when, as in the first war, the Ministry of Food again commandeered the entire country`s crop of raspberries to be used for jam for the troops and the fruit sent to wherever it was required. However, even before the first war, raspberries from Scotland had been exported all the way to Germany. A whole week’s production would go by rail to Leith docks then by ship to ports in Holland then back on rail to Germany. It was apparently wanted for wine production and would, you would think, be well on the way to becoming wine by the time it reached its destination. A Mr Hodge from Blairgowrie who published a book in 1921 on the history of raspberry production in Scotland remarked ”By the time the fruit reached Germany it would be in a fairly liquorish condition but it did not seem to be detrimental to the German physique. lt may have been something to do with the moral deficiencies of the German people"`. This trade would of course cease with the advent of war and, who knows, these comments may have contributed to the reasons for conflict.

Hartleys jam factory in Liverpool. The berries were transported in 1 cwt (112 pounds) wooden barrels which had previously been used to transport salt herring from many of the east coast fishing ports, to the Baltic countries. The barrels went south on the late afternoon train and the empties returned next morning. This trade would cease during the war when, as in the first war, the Ministry of Food again commandeered the entire country`s crop of raspberries to be used for jam for the troops and the fruit sent to wherever it was required. However, even before the first war, raspberries from Scotland had been exported all the way to Germany. A whole week’s production would go by rail to Leith docks then by ship to ports in Holland then back on rail to Germany. It was apparently wanted for wine production and would, you would think, be well on the way to becoming wine by the time it reached its destination. A Mr Hodge from Blairgowrie who published a book in 1921 on the history of raspberry production in Scotland remarked ”By the time the fruit reached Germany it would be in a fairly liquorish condition but it did not seem to be detrimental to the German physique. lt may have been something to do with the moral deficiencies of the German people"`. This trade would of course cease with the advent of war and, who knows, these comments may have contributed to the reasons for conflict.

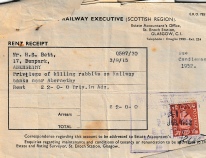

Livestock was another agricultural cargo with both cattle and sheep coming in by rail. Drafts of mainly Irish cattle which had come in to Glasgow by boat would then come by train and stand in the lairage on the north side until being driven to local farms such as Cordon, Balgonie and Jamesfield. Sheep from sales in the north of Scotland would also arrive to be fattened in this area. Another item of livestock sent off from Abernethy was rabbits. Rabbits were plentiful at this time and were a valuable food source especially during the war years, and Abernethy had several trappers, including my uncle, who would snare the rabbits during the winter months. The gutted rabbits would be hung from rails in couples in coffin-like boxes and taken by my father to the station to be sent to game dealers all over the country. The farmer would get a small rent for allowing the trappers on his land and at the same time keeping the crop-damaging beasties’ numbers do wn. The railway company also rented out lengths of the embankments to anyone who wanted to trap or shoot rabbits, and here is a receipt showing that my uncle did just this. l have even seen goats tethered on the embankments to the east of the station to keep the vegetation down. Their tethers being only as long as to reach the top of the bank but not as far as the rails. One final item of livestock, if you could call it that, which l doubted but which my father assured me was true, was when occasionally guests at the "Big Hoose" at Carpow would shoot rooks. They would be sent back to their homes in England to make Crow Pie. So you can be relieved that the ”Four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie" were not the blackies that come to your bird table but were in fact rooks. Too bad for the rooks though. Between the wars another unusual import to Abernethy was "Glescae Dung”. This was the all encompassing contents of the middens used by the people living in Glasgow tenements. Farmers took wagons of this material and it was spread on the fields and ploughed in. Excellent organic fertiliser that lan Miller would grab with both hands, although maybe not literally, if it was available today. The people of Abernethy would I am sure on a warm day also get the benefit of its aroma. Surely like today, if you choose to live in the countryside, the smells of the countryside are a small price to pay for the pleasure of living in such a beautiful and peaceful place.

wn. The railway company also rented out lengths of the embankments to anyone who wanted to trap or shoot rabbits, and here is a receipt showing that my uncle did just this. l have even seen goats tethered on the embankments to the east of the station to keep the vegetation down. Their tethers being only as long as to reach the top of the bank but not as far as the rails. One final item of livestock, if you could call it that, which l doubted but which my father assured me was true, was when occasionally guests at the "Big Hoose" at Carpow would shoot rooks. They would be sent back to their homes in England to make Crow Pie. So you can be relieved that the ”Four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie" were not the blackies that come to your bird table but were in fact rooks. Too bad for the rooks though. Between the wars another unusual import to Abernethy was "Glescae Dung”. This was the all encompassing contents of the middens used by the people living in Glasgow tenements. Farmers took wagons of this material and it was spread on the fields and ploughed in. Excellent organic fertiliser that lan Miller would grab with both hands, although maybe not literally, if it was available today. The people of Abernethy would I am sure on a warm day also get the benefit of its aroma. Surely like today, if you choose to live in the countryside, the smells of the countryside are a small price to pay for the pleasure of living in such a beautiful and peaceful place.

Passenger traffic of course played an important part in the story of the station. Before buses became more frequent, rail travel was the only way to travel unless by horse and cart or by foot. My uncle told me of driving sheep by foot to be sold in the old Hay`s market at Glover Street when he was just a laddie. A Mr Sutherland who worked for my grandfather was in charge, and after delivering the sheep the boys would get the train home but there was no way Mr Sutherland was going to risk life and limb on a train. He would walk all the way back again. lf you wanted to go to Edinburgh you took the train to Bridge of Earn and got the connection from Perth, travelling up the steep Balmanno Hill stretch and through the Glenfarg tunnel and on to the Forth Bridge. Perth was an important rail hub, and where Tesco’s Edinburgh Road shop is now was a great area of sidings, where the locomotives were bunkered with water and coal and where there was a huge turntable to allow the engines to change direction. Travelling east most of the Fife coast towns were served by rail and one of my earliest memories was travelling to Dundee by the North Fife line, now long closed, and over the Tay Bridge. Travelling to Cupar after Lindores, you can see where it ran with some of the track still visible and where the bridges were. Another early trip l remember was to Bridge of Earn station and then walking out to Pitkeathly Wells on the Forgandenny road to "Take the Waters " and enjoy a cup of tea and a cake at the wee tea shop beside the Wells. Pupils travelling to Perth for their secondary education travelled by train until passenger services ceased in 1950, sadly the year l was due to go. The carriages at this time on local trains had individual carriages not corridors and we young laddies were intrigued by tales from older boys of what went on with the girls, especially in the darkness going through Moncrieffe Tunnel. l have asked Janet Paton about this but her lips are sealed. However, she couldn’t conceal a knowing smile and l`m sure she blushed! Sadly l would never find out.

Goods traffic although much reduced would continue until around 1965 by which time l was now the coal merchant. Deliveries continued to Newburgh station for a further period before it was also closed and deliveries then came by road. The station offices then became a house and my story comes to its end after covering much more than was my first intention. l hope any of my contemporaries reading this will vouch that my recall is reasonably accurate but l will stand corrected if they say otherwise. For the rest of the "Crier” readers I hope you have enjoyed sharing my memories with me.